In part to be contrary, I’m going to suggest that to get this nation moving in a positive direction, we need to have a radical discussion about the basic economic realities that most Americans are facing, including the impact of race and class in our hyper-stratified society.

In part to be contrary, I’m going to suggest that to get this nation moving in a positive direction, we need to have a radical discussion about the basic economic realities that most Americans are facing, including the impact of race and class in our hyper-stratified society.

This is not to say that tackling the tax reform-redistricting-lobbying-campaign finance nexus wouldn’t be a good idea. The way money flows through our government and those tasked with running it is truly embarrassing. I fully expect that Clinton and Jacob will do a fine job of addressing these issues. But by and large the differences these issues make are at the margins. They are about how the relative power of the middle-class, the wealthy, the super wealthy, and the inconceivably wealthy. But there’s another half of America out there, which also deserve treatment as full citizens.

If I could start a serious new conversation it would be about the way in which race and class work together to keep many Americans stuck in place while only a few enjoy the bounty our nation has to offer. Contrary to our image as the land of unfettered opportunity, the United States right now is a place in which economic mobility is scarce. Race and class play an outsize role in the land of the free.

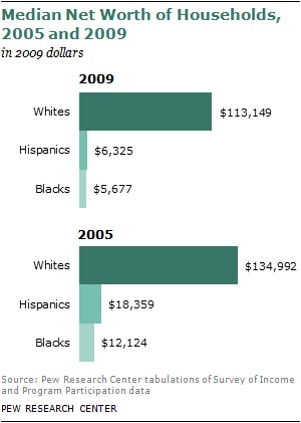

Let me give you two quick examples of what I mean. First, regarding race, consider this chart from a Pew Research study released in 2011:

Yes, you are reading that right. The median net worth of white households was almost 20 times the median net worth of black households. Hispanic households faired only a bit better. Even if we could set everything else aside, that wealth gap alone will make a huge difference in the future of members of that household – in terms of financial planning, educational achievement, entrepreneurialism, retirement, job opportunities, physical mobility, etc. For a fuller, and masterful, treatment of the ways in which recent U.S. housing policies created, maintained, and perpetuated racial outcomes like the ones represented in this chart, I’ll point you to “The Case for Reparations” by Ta-Nehisi Coates. (See also his four–part narrative bibliography of the project and the video TL;DR version.)

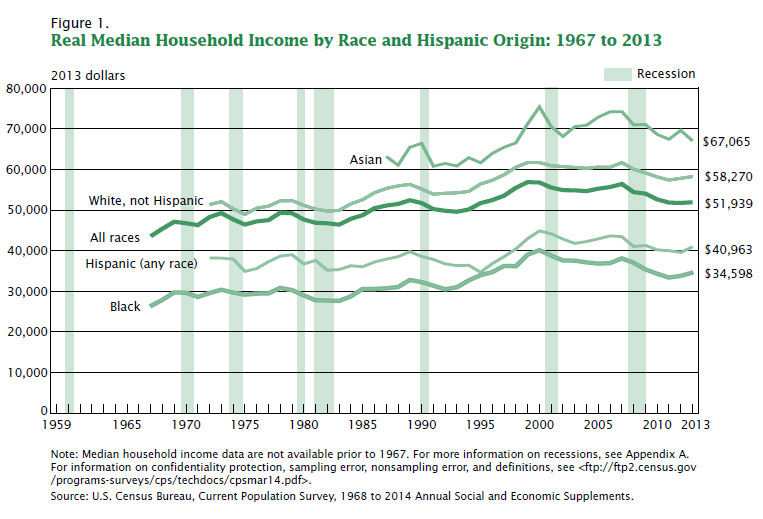

In terms of class, consider the combination of stagnant household medium income (below, from the U.S. Census) and low levels of economic mobility found in the latest studies (in which we lag significantly behind other ‘developed’ nations).

Again, this is not the “land of opportunity” that our best ideals would make it out to be. Do some people succeed, despite these racial and class factors? Of course. My two favorite examples are men named Barack Hussein Obama and Clarence Thomas. But this is not Lake Wobegon, in which we can expect all the children to be above average. And this is just the economic picture.

I teach U.S. history. It is impossible to do so, even for the post-Civil War period, without drawing attention to the ways in which U.S. government policy has favored private property rights over economic opportunity and the white citizens over others.

Why haven’t we ever had a full and meaningful conversation about race and class in this nation? Because even raising the questions are painful and the answers can seem impossible. I see this every term with my students, who knowingly shake their heads about Plessy v. Ferguson and are later shocked to see the household wealth chart I included above.

Unfortunately, in American, we have become far too adept at masking the realities of wealth and poverty in our midst. Until we can see the problem, we have little hope of addressing it. To quote Faulkner, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

Latest posts by Jason LaBau (see all)

- Take Down the Confederate Monuments - August 14, 2017

- The Democratic Split - August 10, 2015

- On Lincoln and Our Second Founding - July 6, 2015

I certainly cannot disagree with any of your points, however, I’m left wondering what solutions are available to address your issue. How do you solve these issues exactly? Is it as simple as merely talking to each other about race? I would imagine there a lot of things at play here some which can be fixed while others can not. I suppose what Im trying to get at is this: What is the cause/causes of this discrepancy and what can be done to address it?

Many of the causes go back centuries, to slavery and its aftermath. Much of it has to do with government policies that either intentionally held back a group of citizens on account of race while in other instances it is more about lost opportunities to actually help.

But lots of this, especially in terms of household wealth, has much more to do with recent government policy (written into the New Deal) that was designed to limit the best government assistance to whites. There are plenty of people alive today who can directly trace their poverty to U.S. government programs that benefited white people while shutting out blacks. As a start, we should address those wrongs.

Ta-Nehisi Coates’ pieces provide the best overview of this that I’ve seen.

Those figures are pretty shocking–it’s incredible how little the national narrative of opportunity corresponds to financial reality. This is a difficult set of issues, and reminds me of an article I read a week or so ago (about global poverty, not limited to the US)–http://aeon.co/magazine/society/to-end-inequality-we-must-understand-how-poverty-works/. Interestingly, the author writes that minority status is the single biggest predictor of poverty, across nations and cultures. The author further argues that one of the big obstacles hindering us from better addressing poverty is that we know shockingly little about the poor (as so much of our inequality discourse and research focuses on the upper end of the spectrum, and outrage against the same)–there’s a pretty convincing argument here that learning more about the world’s/nation’s poorest and redirecting the conversation to really focus on them is a necessary first step toward eradicating poverty.

Thanks for sharing this international perspective. I’m looking forward to reading the article you shared.

My instinct lately has been the same; that all the talk about the 1% or the 10% misses the real issue and elides the real divides. Yes, the wealthy bear a great responsibility, as do corporations, but for the most part all of the non-poor have been complicit in the larger outcomes.

Hopefully in future weeks we can delve a little deeper into this as I’d love to get a much more in depth feel for your side of the equation.

Once the idea of solutions starts being talked about, my mind just can’t grasp a solution that isn’t punishing (in the form of extra taxation or missed educational/vocational opportunities) an existing ‘innocent’ group to award reparations.

So the question is, on account of my being white, should I be forced to pay for the sins of people of my same skin color from the past? While a charged statement, I don’t mean to imply that it’s a purely ridiculous notion. I, truthfully, would like to hear the sales pitch. What is the argument that would require me to fix the past? It’s a place where we often see disagreement. Should the government be tasked with perfecting the history of the world and human psychology, or should we abandon where it’s taken us and start over from a more ideal methodology (libertarian).

While I think this would serve best as a topic for future discussion, I will give you a little spoiler for my thoughts. America was never a place where everyone was promised outcomes. What made America the land of opportunity was : available land and limited government intervention (my opinion). So, if we created a similar landscape today, then it should have a similar outcome to all (not just the privileged races from the last time america presented the opportunity).

I’d love to dive deeper into this, though it would certainly take at least another blog post (not just a comment).

Regarding your argument for need to start fresh and leave the past behind, I’ve been thinking about this hypothetical: Suppose you woke up this morning to find that last night the government had used some legal means to transfer all of your assets (but none of your debt) to your neighbor. But today was the first day in which a newly shrunken government no longer had the power to move back those funds – not through the courts, not through legislation, not in any way – as the result of a push by libertarians to keep government out of wealth (re)distribution. Would you consider that just or fair? Would you really be willing to shrug your shoulders and say “Well, it’s in the past”? And since your neighbor didn’t ASK to get all your money, why should he have to pay to make things right?

Similarly, in ways big and small, our government has systematically ripped off, short changed, and disadvantaged members of our republic. As appealing as a fresh start is, I don’t think we get there by ignoring the past. To me, that wouldn’t be a clean slate. Nor do I think it would be reasonable to expect that everything would just work out for those who have been disadvantaged by the system so far. But then, I’m more suspicious of the power of capital and the markets than libertarians are generally.